TypeScript allows us to create a new type from the existing types, and we can use the utility types for such transformation.

There are various utility types that exist in TypeScript, and we can use any utility type according to our requirements of the type transformation.

Let’s discus the different utility types with examples in TypeScript.

Partial Type in TypeScript

The Partial utility type transforms all the properties of the current type to optional. The meaning of the partial is either all, some, or none. So, it makes all properties optional, and users can use it while refactoring the code with objects.

Example

In the example below, we have created the Type containing some optional properties. After that, we used the Partial utility type to create a partialType object. Users can see that we havent initialized all the properties of the partialType object, as all properties are optional.

type Type ={

prop1: string;

prop2: string;

prop3: number;

prop4?: boolean;};let partialType: Partial<Type>={

prop1:"Default",

prop4:false,};

console.log("The value of prop1 is "+ partialType.prop1);

console.log("The value of prop2 is "+ partialType.prop2);

On compiling, it will generate the following JavaScript code

var partialType ={

prop1:"Default",

prop4:false};console.log("The value of prop1 is "+ partialType.prop1);console.log("The value of prop2 is "+ partialType.prop2);

Output

The above code will produce the following output

The value of prop1 is Default

The value of prop2 is undefined

Required Type in TypeScript

The Required utility type allows us to transform type in such a way that it makes all properties of the type required. When we use the Required utility type, it makes all optional properties to required properties.

Example

In this example, Type contains the prop3 optional property. After transforming the Type using the Required utility operator, prop3 also became required. If we do not assign any value to the prop3 while creating the object, it will generate a compilation error.

type Type ={

prop1: string;

prop2: string;

prop3?: number;};let requiredType: Required<Type>={

prop1:"Default",

prop2:"Hello",

prop3:40,};

console.log("The value of prop1 is "+ requiredType.prop1);

console.log("The value of prop2 is "+ requiredType.prop2);

On compiling, it will generate the following JavaScript code

var requiredType ={

prop1:"Default",

prop2:"Hello",

prop3:40};console.log("The value of prop1 is "+ requiredType.prop1);console.log("The value of prop2 is "+ requiredType.prop2);

Output

The above code will produce the following output

The value of prop1 is Default

The value of prop2 is Hello

Pick Type in TypeScript

The Pick utility type allows us to pick a type of properties of other types and create a new type. Users need to use the key of the types in the string format to pick the key with their type to include in the new type. Users should use the union operator if they want to pick multiple keys with their type.

Example

In the example below, we have picked the color and id properties from type1 and created the new type using the Pick utility operator. Users can see that when they try to access the size property of the newObj, it gives an error as a type of newObj object doesnt contain the size property.

type type1 ={

color: string;

size: number;

id: string;};let newObj: Pick<type1,"color"|"id">={

color:"#00000",

id:"5464fgfdr",};

console.log(newObj.color);// This will generate a compilation error as a type of newObj doesn't contain the size property// console.log(newObj.size);

On compiling, it will generate the following JavaScript code

var newObj ={

color:"#00000",

id:"5464fgfdr"};console.log(newObj.color);// This will generate a compilation error as a type of newObj doesn't contain the size property// console.log(newObj.size);

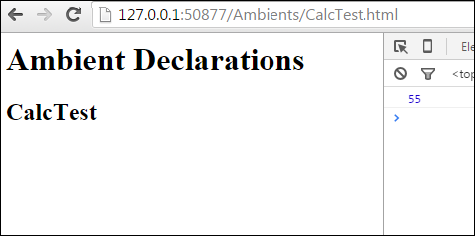

Output

The above code will produce the following output

#00000

Omit Type in TypeScript

The Omit removes the keys from the type and creates a new type. It is the opposite of the Pick. Whatever key we use with the Omit utility operator removes those keys from the type and returns a new type.

Example

In this example, we have omitted the color and id properties from the type1 using the Omit utility type and created the omitObj object. When a user tries to access the color and id properties of omitObj, it will generate an error.

type type1 ={

color: string;

size: number;

id: string;};let omitObj: Omit<type1,"color"|"id">={

size:20,};

console.log(omitObj.size);// This will generate an error// console.log(omitObj.color);// console.log(omitObj.id)

On compiling, it will generate the following JavaScript code

var omitObj ={

size:20};console.log(omitObj.size);// This will generate an error// console.log(omitObj.color);// console.log(omitObj.id)

Output

The above code will produce the following output

20

Readonly Type in TypeScript

We can use the Readonly utility type to make all types read-only properties, making all properties immutable. So, we cant assign any value to the readonly properties after initializing for the first time.

Example

In this example, keyboard_type contains three different properties. We have used the Readonly utility type to make all properties of keyboard objects read-only. The read-only property means we can access it to read values, but we cant modify or reassign them.

type keyboard_type ={

keys: number;

isBackLight: boolean;

size: number;};let keyboard: Readonly<keyboard_type>={

keys:70,

isBackLight:true,

size:20,};

console.log("Is there backlight in the keyboard? "+ keyboard.isBackLight);

console.log("Total keys in the keyboard are "+ keyboard.keys);// keyboard.size = 30 // this is not allowed as all properties of the keyboard are read-only

On compiling, it will generate the following JavaScript code

var keyboard ={

keys:70,

isBackLight:true,

size:20};console.log("Is there backlight in the keyboard? "+ keyboard.isBackLight);console.log("Total keys in the keyboard are "+ keyboard.keys);// keyboard.size = 30 // this is not allowed as all properties of the keyboard are read-only

Output

The above code will produce the following output

Is there backlight in the keyboard? true

Total keys in the keyboard are 70

ReturnType Type in TypeScript

The ReturnType utility type allows to set type for any variable from the functions return type. For example, if we use any library function and dont know the function’s return type, we can use the ReturnType utility operator.

Example

In this example, we have created the func() function, which takes a string as a parameter and returns the same string. We have used the typeof operator to identify the function’s return type in the ReturnType utility operator.

functionfunc(param1: string): string {return param1;}// The type of the result variable is a stringlet result: ReturnType<typeof func>=func("Hello");

console.log("The value of the result variable is "+ result);

On compiling, it will generate the following JavaScript code

functionfunc(param1){return param1;}// The type of the result variable is a stringvar result =func("Hello");console.log("The value of the result variable is "+ result);

Output

The above code will produce the following output

The value of the result variable is Hello

Record Type in TypeScript

The Record utility type creates an object. We need to define the object’s keys using the Record utility type, and it also takes the type and defines the object key with that type of object.

Example

In the example below, we have defined the Employee type. After that, to create a new_Employee object, we used Record as a type utility. Users can see that the Record utility creates an Emp1 and Emp2 object of type Employee in the new_Employee object.

Also, users can see how we have accessed the properties of Emp1 and Emp2 objects of the new_Employee object.

type Employee ={

id: string;

experience: number;

emp_name: string;};let new_Employee: Record<"Emp1"|"Emp2", Employee>={

Emp1:{

id:"123243yd",

experience:4,

emp_name:"Shubham",},

Emp2:{

id:"2434ggfdg",

experience:2,

emp_name:"John",},};

console.log(new_Employee.Emp1.emp_name);

console.log(new_Employee.Emp2.emp_name);

On compiling, it will generate the following JavaScript code

var new_Employee ={

Emp1:{

id:"123243yd",

experience:4,

emp_name:"Shubham"},

Emp2:{

id:"2434ggfdg",

experience:2,

emp_name:"John"}};console.log(new_Employee.Emp1.emp_name);console.log(new_Employee.Emp2.emp_name);</code></pre>

Output

The above code will produce the following output

Shubham

John

NonNullable Type in TypeScript

The NonNullable utility operator removes the null and undefined values from the property type. It ensures that every variable exists with the defined value in the object.

Example

In this example, we have created the var_type, which can also be null or undefined. After that, we used var_type with a NonNullable utility operator, and we can observe that we cant assign null or undefined values to the variable.

type var_type = number | boolean |null|undefined;let variable2: NonNullable<var_type>=false;let variable3: NonNullable<var_type>=30;

console.log("The value of variable2 is "+ variable2);

console.log("The value of variable3 is "+ variable3);// The below code will generate an error// let variable4: NonNullable<var_type> = null;

On compiling, it will generate the following JavaScript code

var variable2 =false;var variable3 =30;console.log("The value of variable2 is "+ variable2);console.log("The value of variable3 is "+ variable3);// The below code will generate an error// let variable4: NonNullable = null;

Output

The above code will produce the following output

The value of variable2 is false

The value of variable3 is 30