Header files in C are files with a .h extension that contain definitions of functions, macros, constants, and data types. C provides standard header files with built-in functions and definitions. Similarly, we can also create our own custom header files.

In this chapter, we will learn how to create and include custom header files in C programs. We will cover the following topics one after the other −

- Custom Header File in C

- Creating a Custom Header File

- Understanding Include Guards

- Alternative: #pragma once

- Contents of a Custom Header File

- Best Practices for Custom Headers

Custom Header File in C

A custom header file is a file that we can create by making a new file with a .h extension and adding function declarations, macros, constants, or structure definitions. By including this header file, we can reuse the code or functions defined in it.

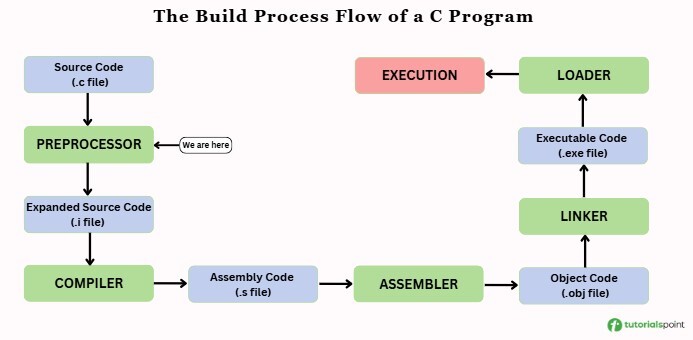

Header files separate declarations from definitions and always have the .h extension. We include them in C source files using the #include directive. For example −

#include "myheader.h"Here, myheader.h is a custom header file.

Creating a Custom Header File

To create a custom header file in C, we write all the function declarations, macros, and constants that we want to reuse in a separate file with the .h extension. Then, we include this header file in our program using the #include directive.

Now, let’s go through the steps to create a custom header file.

Step 1: Create the Header File

Create a file named myheader.h and add the declarations of the functions you want to reuse.

Here’s an example of myheader.h file −

// myheader.h#ifndef MYHEADER_H#define MYHEADER_Hintadd(int a,int b);intsubtract(int a,int b);intmultiply(int a,int b);#endifHere, #ifndef, #define, and #endif are header guards. They make sure the file is not included more than once in a program. In this file, we only write function declarations, not the actual code.

Step 2: Create the Source File

Now, create a file named myheader.c to write the actual code (definitions) for the functions declared in the myheader.h header file.

Here’s an example of the myheader.c file −

// myheader.c#include "myheader.h"intadd(int a,int b){return a + b;}intsubtract(int a,int b){return a - b;}intmultiply(int a,int b){return a * b;}In the above program, we include the “myheader.h” file using #include directive. By including this file, the compiler knows that the functions we are defining match the declarations in the myheader.h header file.

Step 3: Use the Header File in the Main Program

Finally, create the main program file main.c and include the custom header file to use the functions we declared in myheader.h and defined in myheader.c.

Here’s an example of our main.c program, where we include the custom header file (myheader.h) and call the add(), subtract(), and multiply() functions just like we call the built-in functions.

// main.c#include <stdio.h>#include "myheader.h"intmain(){int a =10, b =5;printf("Addition: %d\n",add(a, b));printf("Subtraction: %d\n",subtract(a, b));printf("Multiplication: %d\n",multiply(a, b));return0;}Step 4: Compile the Program

Finally, compile both main.c and myheader.c together so the function definitions are linked with their declarations −

gcc main.c myheader.c -o program

Then, run the program using the following command −

./program

The program will run successfully and display the following output −

Addition: 15

Subtraction: 5

Multiplication: 50

Understanding Include Guards

An important point to note about custom headers is the use of include guards. If the same header file is included multiple times in a program, the compiler may throw errors like redefinition of functions or variables. To prevent this, we wrap the header code inside preprocessor directives called #ifndef, #define, and #endif, which ensure the compiler includes the file only once.

Here’s the general structure of a header guard −

#ifndef FILENAME_H#define FILENAME_H// declarations#endifHere’s an example with a custom header file −

#ifndef MYHEADER_H#define MYHEADER_Hintadd(int a,int b);intsubtract(int a,int b);#endifAlternative: #pragma once

Instead of using include guards, we can also write #pragma once at the top of the header file. For Example −

#pragma onceintadd(int a,int b);intsubtract(int a,int b);It works just like include guards and makes sure the compiler includes the header file only once. Just keep in mind that it is compiler-specific, although most modern compilers support it.

Contents of a Custom Header File

In a custom header file, we can include different kinds of reusable code, such as –

Function Declarations − Declare functions to use them in multiple programs without rewriting.

intadd(int a,int b);intsubtract(int a,int b);Macros − Define constants or small code snippets that the compiler replaces wherever needed.

#define MAX 100#define MIN 0Constants − Store values that do not change, such as mathematical or fixed program values.

constfloat PI =3.14159;constint DAYS_IN_WEEK =7;Structure − Group related data together into a single unit.

structStudent{char name[50];int age;};Unions − Store different types in the same memory location to save memory.

union Data {int i;float f;char str[20];};Enumerations − Define named sets of integer constants.

enumColor{ RED, GREEN, BLUE };Avoid putting full function definitions in the header file except for inline functions, because including them in multiple files can cause errors.

Best Practices for Custom Headers

Here are some important points we should take care of while creating custom header files in C −

- Always use include guards or #pragma once to avoid multiple inclusion errors.

- Keep declarations in .h files and the actual code (definitions) in .c files.

- Give meaningful names to your headers so it’s easy to know what they contain.

- Don’t put too much code in headers. Only write declarations there, unless you are using inline functions.

- Group related functions together in a single header. For example, all math functions can go in mathutils.h.

- Add comments to your headers to explain what each part does.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we learned how to create our own header files in C. Using custom headers helps organize code, improve readability, and make programs easier to manage. They also enable code to be reused across multiple programs, which reduces repetition, saves development time.