In C language, an array is a collection of values of similar type stored in continuous memory locations. Each element in an array (one-dimensional or multi-dimensional) is identified by one or more unique integer indices.

A pointer, on the other hand, stores the address of a variable. The address of the 0th element in an array is the pointer of the array. You can use the “dereference operator” to access the value that a pointer refers to.

You can declare a one-dimensional, two-dimensional or multi-dimensional array in C. The term “dimension” refers to the number of indices required to identify an element in a collection.

Pointers and One-dimensional Arrays

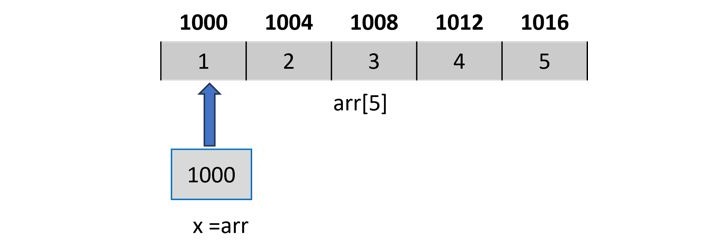

In a one-dimensional array, each element is identified by a single integer:

int a[5]={1,2,3,4,5};Here, the number “1” is at the 0th index, “2” at index 1, and so on.

A variable that stores the address of 0th element is its pointer −

int*x =&a[0];Simply, the name of the array too points to the address of the 0th element. So, you can also use this expression −

int*x = a;Example

Since the value of the pointer increments by the size of the data type, “x++” moves the pointer to the next element in the array.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int arr[]={1,2,3,4,5};int length =sizeof(arr)/sizeof(arr[0]);int i =0;int*ptr = arr;while(i < length){printf("arr[%d]: %d \n", i,*(ptr + i));

i++;}return0;}</code></pre>

Output

When you run this code, it will produce the following output −

arr[0]: 1

arr[1]: 2

arr[2]: 3

arr[3]: 4

arr[4]: 5

Pointers and Two-dimensional Arrays

If a one-dimensional array is like a list of elements, a two-dimensional array is like a table or a matrix.

The elements in a 2D array can be considered to be logically arranged in rows and columns. Hence, the location of any element is decided by two indices, its row number and column number. Both row and column indexes start from "0".

int arr[2][2];

Such an array is represented as −

Col0 Col1 Col2 Row0 arr[0][0] arr[0][1] arr[0][2] Row1 arr[1][0] arr[1][1] arr[1][2] Row2 arr[2][0] arr[2][1] arr[2][2]

It may be noted that the tabular arrangement is only a logical representation. The compiler allocates a block of continuous bytes. In C, the array allocation is done in a row-major manner, which means the elements are read into the array in a row−wise manner.

Here, we declare a 2D array with three rows and four columns (the number in the first square bracket always refers to the number of rows) as −

int arr[3][4]={{1,2,3,4},{5,6,7,8},{9,10,11,12}};

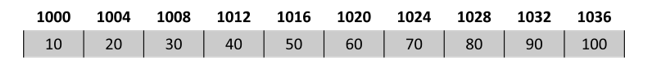

The compiler will allocate the memory for the above 2D array in a row−wise order. Assuming that the first element of the array is at the address 1000 and the size of type "int" is 4 bytes, the elements of the array will get the following allocated memory locations −

Row 0 Row 1 Row 2 Value 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Address 1000 1004 1008 1012 1016 1020 1024 1028 1032 1036 1040 1044

We will assign the address of the first element of the array num to the pointer ptr using the address of & operator.

int*ptr =&arr[0][0];

Example 1

If the pointer is incremented by 1, it moves to the next address. All the 12 elements in the "34" array can be accessed in a loop as follows −

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int arr[3][4]={{1,2,3,4},{5,6,7,8},{9,10,11,12},};// pointer ptr pointing at array numint*ptr =&arr[0][0];int i, j, k =0;// print the elements of the array num via pointer ptrfor(i =0; i <3; i++){for(j =0; j <4; j++){printf("%d ",*(ptr + k));

k++;}printf("\n");}return0;}</code></pre>

Output

When you run this code, it will produce the following output −

1 2 3 4

5 6 7 8

9 10 11 12

In general, the address of any element of the array by with the use the following formula −

add of element at ith row and jth col = baseAddress +[(i * no_of_cols + j)*sizeof(array_type)]

In our 34 array,

add of arr[2][4]=1000+(2*4+2)*4=1044

You can refer to the above figure and it confirms that the address of "arr[3][4]" is 1044.

Example 2

Use the dereference pointer to fetch the value at the address. Let us use this formula to traverse the array with the help of its pointer −

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){// 2d arrayint arr[3][4]={{1,2,3,4},{5,6,7,8},{9,10,11,12}};int ROWS =3, COLS =4;int i, j;// pointerint*ptr =&arr[0][0];// print the element of the array via pointer ptrfor(i =0; i < ROWS; i++){for(j =0; j < COLS; j++){printf("%4d ",*(ptr +(i * COLS + j)));}printf("\n");}return0;}

Output

When you run this code, it will produce the following output −

1 2 3 4

5 6 7 8

9 10 11 12

Pointers and Three-dimensional Arrays

A three-dimensional array is an array of two-dimensional arrays. Such an array is declared with three subscripts −

int arr [x][y][j];

This array can be considered as "x" number of layers of tables, each table having "x" rows and "y" number of columns.

An example of a 3D array is −

int arr[3][3][3]={{{11,12,13},{14,15,16},{17,18,19}},{{21,22,23},{24,25,26},{27,28,29}},{{31,32,33},{34,35,36},{37,38,39}},};

A pointer to the 3D array can be declared as −

int* ptr =&arr[0][0][0];

Knowing that, the name of the array itself is the address of 0th element, we can write the pointer of a 3D array as −

int* ptr = arr;

Each layer of "x" rows and "y" columns occupies −

x * y *sizeof(data_type)

Number of bytes. Assuming that the memory allocated to the 3D array "arr" as declared above starts from the address 1000, the second layer (with "i = 1") starts at 1000 + (3 3) 4 = 1036 byte position.

ptr = Base address of 3D array arr

If JMAX is the number of rows and KMAX is the number of columns, then the address of the element at the 0th row and the 0th column of the 1st slice is −

arr[1][0][0]= ptr +(1* JMAX * KMAX)

The formula to obtain the value of an element at the jth row and kth column of the ith slice can be given as −

arr[i][j][k]=*(ptr +(i * JMAX*KMAX)+(j*KMAX + k))

Example: Printing a 3D Array using Pointer Dereferencing

Let us use this formula to print the 3D array with the help of the pointer dereferencing −

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int i, j, k;int arr[3][3][3]={{{11,12,13},{14,15,16},{17,18,19}},{{21,22,23},{24,25,26},{27,28,29}},{{31,32,33},{34,35,36},{37,38,39}},};int JMAX =3, KMAX =3;int*ptr = arr;// &arr[0][0][0];for(i =0; i <3; i++){for(j =0; j <3; j++){for(k =0; k <3; k++){printf("%d ",*(ptr+(i*JMAX*KMAX)+(j*KMAX+k)));}printf("\n");}printf("\n");}return0;}

Output

When you run this code, it will produce the following output −

11 12 13

14 15 16

17 18 19

21 22 23

24 25 26

27 28 29

31 32 33

34 35 36

37 38 39

In general, accessing an array with a pointer is quite similar to accessing an array with subscript representation. The main difference between the two is that the subscripted declaration of an array allocates the memory statically, whereas we can use pointers for dynamic memory allocation.

To pass a multi-dimensional array to a function, you need to use pointers instead of subscripts. However, using a subscripted array is more convenient than using pointers, which can be difficult for new learners.