In C, the printf() function is used to display the output on the screen and it is defined in the standard I/O library (<stdio.h>), so we need to include this header file at the start of every program to use printf() properly. For example,

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){// code goes herereturn0;}

In this chapter, we’ll cover the printf() function in C and how it works. Below are the topics which we are going to cover −

- printf() in C

- Format specifiers in printf()

- Format String Structure in printf()

- Format Flags in printf()

- Width in printf()

- Precision in printf()

- Length Modifiers in printf() Function

- Escape sequences in printf()

printf() in C

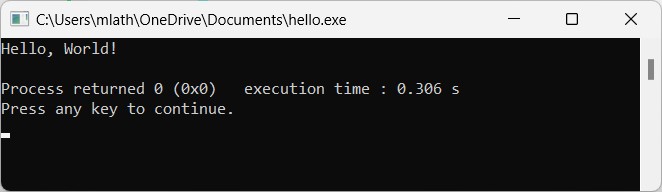

The printf() function in C is a built-in function used for displaying the output on the screen. It can print text, numbers, characters, variables and even formattted data. For example, writing “Hello, World!” inside the printf() function will display exactly that on the screen.

Syntax of printf()

Following is the syntax of printf() function in C −

printf("format_string", args...);

Parameters of printf()

The printf() function takes the following two parameters −

- format_string: It is the message or text we want to display on the screen, and it can include format specifiers (like %d, %f, %c, %s) as placeholders for variables.

- args…: It is the actual values that will replace these placeholders when the program runs.

Return Type of printf()

The return type of printf() function is int. It returns the number of characters printed on the screen or returns a negative value if an error occurred.

Example of printf() in C

Here’s an example of printf() function in C. We define an age variable and assign a value to it. Then we use the printf() function to display a message, where the format string contains %d, which will be replaced by the value of the age variable.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int age =20;printf("Hello! I am %d years old.\n", age);return0;}

Here is the output of the above program, which prints the message and the age.

Hello! I am 20 years old.

Format specifiers in printf() are the placeholders that start with % and we use them inside the printf() function to specify what type of data we want to print. Listed below is a list of common format specifiers –

- %d or %i: Prints an integer (decimal).

- %f: Prints a floating-point number.

- %.2f: Prints a floating-point number with 2 digits after the decimal point.

- %c: Prints a single character.

- %s: Prints a string.

- %u: Prints an unsigned integer.

- %x: Prints a hexadecimal number (lowercase).

- %X: Prints a hexadecimal number (uppercase).

- %p: Prints a pointer (memory address).

- %%: Prints the % symbol itself.

Now let’s look at each of these format specifiers in detail.

Example: Printing an Integer

We use %d or %i to print integers in C, and both specifiers give the same result for decimal values. In the program below, we define a variable num with the value 42 and use both specifiers to print it.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int num =42;printf("Using %%d: The number is %d\n", num);printf("Using %%i: The number is %i\n", num);return0;}

When we run this program, the output will be −

Using %d: The number is 42

Using %i: The number is 42

Example: Printing a Floating-point Number

The %f specifier is used to print floating-point numbers, and it displays values with six digits after the decimal point by default. In the program below, we define a variable pi with the value 3.14159 and use printf() to display it.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){float pi =3.14159;printf("The value of pi is %f", pi);return0;}

The output of this program will be-

The value of pi is 3.141590

Example: Printing a Character

The %c specifier is used to display the single character. In the below program, we define a variable grade and assign it the character ‘A’ and display it using printf().

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){char grade ='A';printf("Your grade is %c", grade);return0;}

Below is the output of the above program using %c specifier −

Your grade is A

Example: Printing a String

We use %s to print a string, which is a collection of characters. In the program below, we define a string variable message and display it in the printf() function.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){char message[]="Welcome to Tutorialspoint";printf("Using %%s specifier: %s\n", message);return0;}

Below is the output of the above program, which displays a message.

Using %s specifier: Welcome to Tutorialspoint

Example: Printing an Unsigned Integer

We use %u to print an unsigned integer, which is a number that cannot be negative. In this program, we create an unsigned integer variable age and display it in the printf() function.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){unsignedint age =25;printf("Using %%u specifier: Age is %u\n", age);return0;}

Following is the output of the above program, which displays the unsigned integer.

Using %u specifier: Age is 25

Example: Printing a Pointer Address

The %p specifier prints the memory address of a variable. In this program, we create an integer variable num and in the printf() funtion we display its address. The output shows the memory location, which can change each time the program runs.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int num =10;printf("Using %%p specifier, Address of num: %p\n",&num);return0;}

Here’s the output of the above program, which displays the memory address where the num variable is stored.

Using %p specifier, Address of num: 0x7ffd54cce62c

Example: Printing a Percent Sign

To print the % symbol itself, we use %% inside printf(). In this program, we define an integer variable marks and display it along with the percent sign.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int marks =90;printf("You scored %d%% in the exam.\n", marks);return0;}

Here is the output of the program, showing the use of %% in printf() to display % −

You scored 90% in the exam.

A format string in the printf() function tells the program how to format data in input/output operations. It can include text and placeholders, and it follows a specific structure starting with %.

Below is the general structure of a format specifier −

%[flags][width][.precision][length]specifier

Each part of the specifier controls how the value is displayed. We will see flags, width, precision, and length in detail with examples below.

In the printf() function, flags are optional characters that we place right after % in a format specifier. They help control how our output looks by adjusting alignment, padding, signs, and prefixes. Here are the main flags −

- – (Minus): Left-aligns the output within the specified width.

- + (Plus): Always prints the sign of a number (+ or –).

- 0 (Zero): Pads the number with leading zeros.

- (Space): Adds a space before positive numbers.

- # (Hash): Adds a prefix (like 0x for hexadecimal or 0 for octal).

We will look at examples of each flag below to see how they actually change the output.

Example: Left Align Using (-) Flag

We will use the – flag to left-align a number within a field of width 5. In the example below, we first print the number without the flag, and then with – flag to see how the alignment changes.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int num =2314;printf("Without flag: |%5d|\n", num);printf("With left-justify: |%-5d|\n", num);return0;}

Here is the output of the above program −

Without flag: | 2314|

With left-justify: |2314 |

Example: Show Sign Using (+) Flag

Below is a compelte C program where we use the + flag to display the sign for both positive and negative numbers.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int pos =1423;int neg =-1423;printf("Without flag: %d, %d\n", pos, neg);printf("With plus flag: %+d, %+d\n", pos, neg);return0;}

Below is the output of the above program.

Without flag: 1423, -1423

With plus flag: +1423, -1423

Example: Pad Numbers With Zeros Using (0) Flag

We will use the 0 flag to pad numbers with leading zeros instead of spaces. We define a number in a field of width 7, then print it first without the flag and then with the 0 flag to see the difference.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int num =14;printf("Without flag: |%7d|\n", num);printf("With zero padding: |%07d|\n", num);return0;}

Following is the output of the above program.

Without flag: | 14|

With zero padding: |0000014|

Example: Add Space Before Positive Numbers ( ) Flag

We use the ( )space flag to add a space before positive numbers and keep negative numbers as they are. In the example below, we’ll see how it changes the alignment of numbers.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int pos =23;int neg =-23;printf("Without space: |%d| |%d|\n", pos, neg);printf("With space flag: |% d| |% d|\n", pos, neg);return0;}

Below is the output of the above program.

Without space: |23| |-23|

With space flag: | 23| |-23|

Example: Alternate Form (#) Flag for Octal and Hex

We will use the # flag to add prefixes to numbers. In the example below, we will use the # flag to display each number in octal and hexadecimal form. The # flag adds 0 before octal numbers, 0x before lowercase hexadecimal, and 0X before uppercase hexadecimal.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int num =2314;printf("Octal without #: %o\n", num);printf("Octal with #: %#o\n", num);printf("Hex lowercase without #: %x\n", num);printf("Hex lowercase with #: %#x\n", num);printf("Hex uppercase without #: %X\n", num);printf("Hex uppercase with #: %#X\n", num);return0;}

Following is the output of the above program −

Octal without #: 4412

Octal with #: 04412

Hex lowercase without #: 90a

Hex lowercase with #: 0x90a

Hex uppercase without #: 90A

Hex uppercase with #: 0X90A

Width in printf()

Width in printf() function sets the minimum space for a value. It adds extra spaces if the value is shorter, and by default, the value is right-aligned. If the value is longer than the width, it prints the full value without adding any space.

Example: Using Width with Integers

Here, we print two integers in a field of width 5 using printf(). The first number has fewer digits, so extra spaces are added, and the second number fits the width, so it prints as it is.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int num1 =23;int num2 =231423;printf("Number 1 with width 5: |%5d|\n", num1);printf("Number 2 with width 5: |%5d|\n", num2);return0;}

Here is the output of the above program −

Number 1 with width 5: | 23|

Number 2 with width 5: |231423|

Precision in printf()

Precision in printf() controls how much of a value is displayed.

- For floating-point numbers, it sets the number of digits after the decimal point.

- For strings, it limits the maximum number of characters to print.

Example: Precision with Float and String

We use %.2f to print a floating-point number with 2 decimal places, and %.5s to print only the first 5 characters of a string. In the following program, we store both a number and a string, then print them using the printf() function.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){float pi =3.14159;char str[]="Tutorialspoint";printf("Pi with 2 decimals: %.2f\n", pi);printf("String with 5 characters: %.5s\n", str);return0;}

When you run this code, it will produce the following output –

Pi with 2 decimals: 3.14

String with 5 characters: Tutor

Length Modifiers in printf() Function

Length modifiers in printf() function are used to specify the size or type of the data we want to print. They are used with format specifiers like %d or %f, and their main purpose is to ensure that numbers of different sizes are handled correctly.

Here are the common length modifiers −

- h: for short numbers.

- l: for long numbers.

- ll: for long long numbers.

- L: for long double numbers

Example: Printing Short and Long Integers

We will use h and l to print short and long integers. In the below example, we define a short integer and a long integer, then print them using %hd and %ld in printf() function.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){short s =32000;long l =1234567890;printf("Short number: %hd\n", s);printf("Long number: %ld\n", l);return0;}

Following is the output of the above program −

Short number: 32000

Long number: 1234567890

Example: Printing Long Long and Long Double

We will use ll and L to print long long integers and long doubles. In the below example, we define a long long integer and a long double, then print them using %lld and %Lf in printf() function.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){longlong ll =123456789012345;longdouble ld =3.141592653589793238;printf("Long long number: %lld\n", ll);printf("Long double: %.15Lf\n", ld);return0;}

Here you can see the output of the above program −

Long long number: 123456789012345

Long double: 3.141592653589793

Escape sequences in printf()

Escape sequences are special characters that start with a backslash (\). We use them to control the output format, like moving to a new line or adding tabs. Escape sequences in C are case-sensitive, so \n is different from \N.

Some commonly used escape sequences are:

- \n :moves the cursor to the next line.

- \t :adds a horizontal tab.

- \\ :prints a backslash.

- \” :prints a double quote.

Let’s look at examples to understand how we can use these escape sequences with printf() function.

Printing a New Line

We use \n to move text to the next line. In the example below, we print “Welcome to Tutorialspoint” on two lines using \n in printf().

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){printf("Welcome to\Our App

");return0;}

In the output below, we can see that the message is printed in two lines −

Welcome to

Our App

Example: Using Tab and Quotes

We use \t to add a tab space and \” to print quotes in the output. In the example below, we format a list of items with their prices using tabs and quotes.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){printf("Item\tPrice\n");printf("\"Book\"\t$12\n");printf("\"Pen\"\t$2\n");return0;}

Here’s the output of the above program −

Item Price

"Book" $12

"Pen" $2

Example: Using Multiple Specifiers with Escape Sequences

We will use multiple format specifiers along with escape sequences to print numbers, floats and characters. In the example below, we print age, GPA, and grade in a single line using %d, %.2f, and %c. We also use \n to move to the next line and \t to add a tab for better formatting.

#include <stdio.h>intmain(){int age =20;float gpa =8.75;char grade ='A';printf("Age:\t%d\nGPA:\t%.2f\nGrade:\t%c\n", age, gpa, grade);return0;}

Below you can see the output displayed with proper formatting −

Age: 20

GPA: 8.75

Grade: A

Conclusion

In this chapter, we explained in detail the printf() function in C, which is used to display the output on the screen. We highlighted how to use format specifiers to print different types of data. Additionally, we covered features like flags, width, precision, length modifiers, and escape sequences to format the output using the printf() function.