In a multi-process system, deadlock is an unwanted situation that arises in a shared resource environment, where a process indefinitely waits for a resource that is held by another process.

For example, assume a set of transactions {T0, T1, T2, …,Tn}. T0 needs a resource X to complete its task. Resource X is held by T1, and T1 is waiting for a resource Y, which is held by T2. T2 is waiting for resource Z, which is held by T0. Thus, all the processes wait for each other to release resources. In this situation, none of the processes can finish their task. This situation is known as a deadlock.

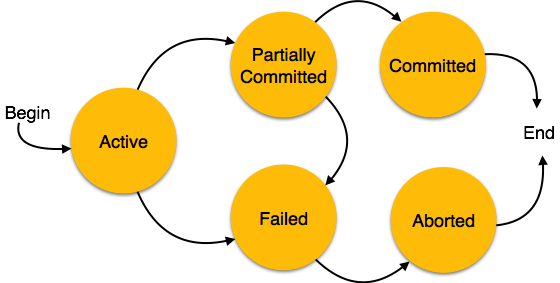

Deadlocks are not healthy for a system. In case a system is stuck in a deadlock, the transactions involved in the deadlock are either rolled back or restarted.

Deadlock Prevention

To prevent any deadlock situation in the system, the DBMS aggressively inspects all the operations, where transactions are about to execute. The DBMS inspects the operations and analyzes if they can create a deadlock situation. If it finds that a deadlock situation might occur, then that transaction is never allowed to be executed.

There are deadlock prevention schemes that use timestamp ordering mechanism of transactions in order to predetermine a deadlock situation.

Wait-Die Scheme

In this scheme, if a transaction requests to lock a resource (data item), which is already held with a conflicting lock by another transaction, then one of the two possibilities may occur −

- If TS(Ti) < TS(Tj) − that is Ti, which is requesting a conflicting lock, is older than Tj − then Ti is allowed to wait until the data-item is available.

- If TS(Ti) > TS(tj) − that is Ti is younger than Tj − then Ti dies. Ti is restarted later with a random delay but with the same timestamp.

This scheme allows the older transaction to wait but kills the younger one.

Wound-Wait Scheme

In this scheme, if a transaction requests to lock a resource (data item), which is already held with conflicting lock by some another transaction, one of the two possibilities may occur −

- If TS(Ti) < TS(Tj), then Ti forces Tj to be rolled back − that is Ti wounds Tj. Tj is restarted later with a random delay but with the same timestamp.

- If TS(Ti) > TS(Tj), then Ti is forced to wait until the resource is available.

This scheme, allows the younger transaction to wait; but when an older transaction requests an item held by a younger one, the older transaction forces the younger one to abort and release the item.

In both the cases, the transaction that enters the system at a later stage is aborted.

Deadlock Avoidance

Aborting a transaction is not always a practical approach. Instead, deadlock avoidance mechanisms can be used to detect any deadlock situation in advance. Methods like “wait-for graph” are available but they are suitable for only those systems where transactions are lightweight having fewer instances of resource. In a bulky system, deadlock prevention techniques may work well.

Wait-for Graph

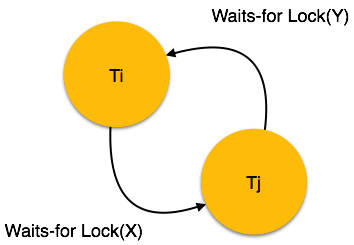

This is a simple method available to track if any deadlock situation may arise. For each transaction entering into the system, a node is created. When a transaction Ti requests for a lock on an item, say X, which is held by some other transaction Tj, a directed edge is created from Ti to Tj. If Tj releases item X, the edge between them is dropped and Ti locks the data item.

The system maintains this wait-for graph for every transaction waiting for some data items held by others. The system keeps checking if there’s any cycle in the graph.

Here, we can use any of the two following approaches −

- First, do not allow any request for an item, which is already locked by another transaction. This is not always feasible and may cause starvation, where a transaction indefinitely waits for a data item and can never acquire it.

- The second option is to roll back one of the transactions. It is not always feasible to roll back the younger transaction, as it may be important than the older one. With the help of some relative algorithm, a transaction is chosen, which is to be aborted. This transaction is known as the victim and the process is known as victim selection.