In database management, there are plenty of different techniques to store files for easy access and optimized use-cases. Two of the most common types of file organizations are unordered records (heap files) and ordered records (sorted files), each with their own strengths, weaknesses, and use cases.

Read this chapter to learn in detail the concepts of unordered and ordered files, explore their differences, and see real-world examples of how they are used.

Unordered Records: The Heap File

Unordered records or heap files are nothing but a dump. Heap files are the simplest form of file organization. The records are stored in the order they are inserted. When a new record is added, it is placed at the end of the file. This process makes the insertion quick and straightforward.

How Do Heap Files Work?

Let’s see how heap files work −

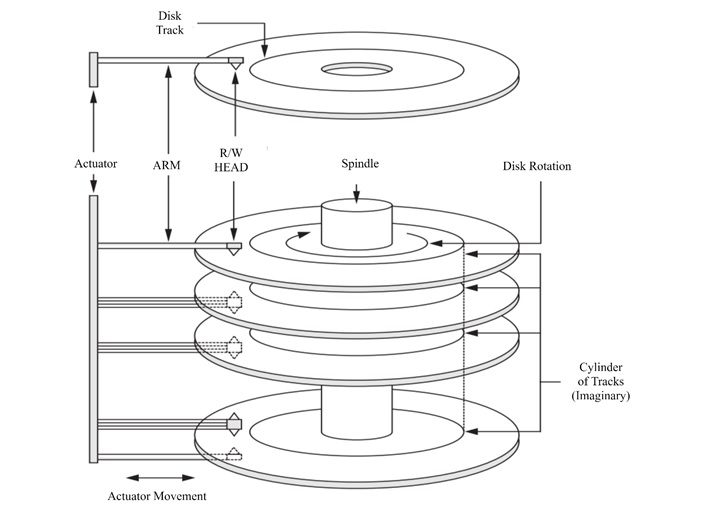

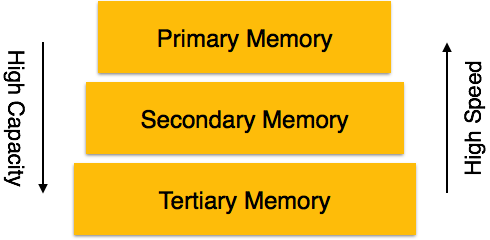

- When a record is inserted, the last disk block of the file is loaded into memory. Here the new record is appended. The block is written back to the disk.

- The address of the last block is maintained in the file header. It gives quick access for new inserts.

Advantages of Using Heap Files

Following are the advantages of using heap files −

- Quick Insertions − Adding a record is very efficient, since no sorting or restructuring is applied.

- Simplicity − The structure is straightforward and it requires minimal overhead.

Limitations of Heap Files

Heap files are simple and easy to maintain, but they have their own limitations −

- Linear Search for Retrieval − To find a specific record, we need to rely on a linear search through all blocks. On an average, half the blocks must be searched, which makes the retrieval process slow for large files.

- Wasted Space − Deleting a record leaves unused space in the block unless the file is reorganized periodically.

- Inefficient Updates − Updates such as modifying some variable-length records, deleting an old record and inserting a new one can further fragment the file.

Handling Deletions in Heap Files

One way to handle deletions in heap files is by using a deletion marker. Here, each record has a small flag (a byte or a bit) to indicate whether it is active or deleted. When a record is marked as deleted, it remains in the file but is ignored during searches. Periodically, the file is reorganized to reclaim space and remove deleted records.

Ordered Records: The Sorted File

Ordered records are sorted and organized based on the values of a specific field which is known as the ordering field. If this field is unique for each record, it is called the ordering key. This type of file organization makes searches and sequential access faster, however it comes with its challenges for insertions and deletions.

How Do Ordered Records Work?

Records are stored in ascending or descending order of the ordering field. For example, an employee database might be sorted alphabetically by employee names. The records are placed in blocks, and the blocks are organized contiguously on the disk.

Advantages of Ordered Records

Given below are some of the advantages of using ordered records −

- Efficient Searches − We can use binary search or other fast search techniques, as the system can quickly locate a record based on the ordering field. For example, if the file has 100 blocks, a binary search requires only about 7 block accesses on average.

- Easy Sequential Access − It’s easy to access ordered records since the blocks are stored contiguously.

- Sorting for Queries − Ordered records simplify certain queries, such as finding all employees whose names start with a specific letter.

Limitations of Ordered Records

While retrieval of data is efficient in ordered records, updates and modifications are not so easy. Given below are some other notable limitations of using ordered records −

- Insertion Complexity − To insert a new record, the correct position in the file must be located. It requires shifting many records to make space, which is time-consuming for large files.

- Costly Deletions − Deleting a record leaves a gap. It requires reorganization to maintain order. Using a deletion marker can delay reorganization but does not eliminate the overhead.

- Overflow Files − To address insertion delays, we can add new records and they are often stored in a temporary unordered file (overflow file). Periodically, the overflow file is merged with the main file. This is a resource-intensive process.

Example: Binary Search in a Sorted File

Imagine an ordered file of employee records, sorted by names. The file has 100 blocks. We want to find the employee named Amit Mondal. Using a binary search, we can do the following −

- The system starts with the middle block, say block 50, and checks if Amitâs name falls before or after the names in that block.

- If Amitâs name is alphabetically before, the search narrows to blocks 1â49; otherwise, it checks blocks 51â100.

- This process continues, halving the range with each step, until the record is found or all possibilities are exhausted.

- This method requires only log2(100) â 7 block accesses, which is much faster than the linear search required for heap files.

Differences between Unordered and Ordered Files

The following table highlights the key differences between ordered and unordered files −

| Aspect | Unordered Records (Heap Files) | Ordered Records (Sorted Files) |

|---|---|---|

| Insertion | Faster; new records are added to the end of the file | Slower; inserting requires finding the correct position |

| Search | Linear search; slow for large files | Binary search; much faster for ordering field |

| Deletion | Leaves gaps; periodic reorganization needed | Gaps also require reorganization, or use of overflow files |

| Modification | Simple for fixed-length records | Complex if ordering field changes |

| Sequential Access | Inefficient; requires sorting first | Very efficient due to physical ordering |

Overflow Files

To speed up insertions, new records are stored in an overflow file. For example −

- The main file contains records sorted by names; the overflow file, on the other hand, holds unsorted new records.

- Periodically, the overflow file is merged with the main file, which is needed to ensure the overall file remains ordered.

External Sorting

For very large files, sorting them entirely in memory is impractical. Now external sorting techniques divide the file into smaller chunks, sort each chunk, and then merge them together. This process is quite useful and the file remains ordered without overwhelming system resources.

When to Use Unordered vs. Ordered Files

Unordered files are suitable for applications where insertions are frequent, and searches are infrequent or involve scanning the entire file (e.g., collecting log data for later analysis).

Ordered files are ideal when efficient searches based on a specific field are needed, or when sequential access is common (e.g., payroll processing by employee names).